Reflections on

a Career in

Echocardiography

By James D. Thomas,

MD, FASE, FACC, FESC

Professor of Medicine (Cardiology) at Northwestern Medicine

James D. Thomas, MD, is a cardiologist at Northwestern Medicine with a clinical focus in valvular heart disease and echocardiography and extensive research into applying physical principles and advanced technology in cardiovascular imaging. He now serves as Director for the Center for Heart Valve Disease and Academic Affairs in the Bluhm Cardiovascular Institute and co-directs the Center for Artificial Intelligence in Cardiovascular Disease while serving as Professor of Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Born and raised in Oklahoma City, Dr. Thomas attended Harvard College (graduating summa cum laude in Applied Mathematics) and Harvard Medical School before clinical training at Massachusetts General Hospital and the University of Vermont.

Dr. Thomas has over 650 peer reviewed publications with an h-index of 135. He is past-president of the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) and co-chairs a committee to standardize the measurement of myocardial strain by echocardiography. He previously served on the Cardiovascular Board of the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) and as co-chairman for the 2007 American College of Cardiology (ACC) Annual Scientific Sessions. Dr. Thomas also serves as lead scientist for ultrasound with NASA, focusing on the effects of space on cardiovascular function. Other research interests include cardiac mechanics, application of new echocardiography technology, artificial intelligence and integration of engineering principles into clinical decision-making.

Since arriving at Northwestern, Dr. Thomas has been instrumental in bringing early device trials to BCVI and providing intraprocedural echo guidance for cath lab interventions. He has also formed a two-year fellowship in advanced cardiovascular imaging and another in artificial intelligence in collaboration with engineers and scientists on the Evanston campus.

When not reading echoes, Dr. Thomas enjoys cooking, skiing, scuba diving, and the occasional bungee jump.

James D. Thomas, MD, FACC, FASE, FESC

Cardiology, Imaging & Valvular Heart Disease

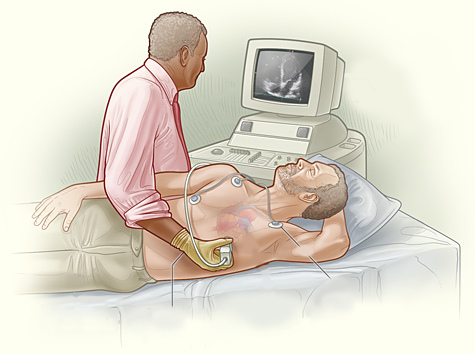

I recall the first time I really saw the diagnostic power of echocardiography. I was a third-year medical student at Harvard and was on my first clerkship (in medicine) at the Beth Israel Hospital, and Dr. Patricia Come was using an M-mode probe to diagnose endocarditis in an elderly man. I was fascinated that those inscrutable squiggles could actually tell us something, but also recall an equally deep conviction that I would NEVER want to be the “echo guy”. Well, fast forward some 4 decades, and I guess that’s what I’ve mainly been, and it’s been a fascinating ride, with every year bringing new discoveries and new technological breakthroughs. It continues today, with Moore’s Law and Deep Learning powering the acquisition and interpretation of echo with artificial intelligence.

By the time I was a cardiology fellow at the University of Vermont, echo had come a long way, with 2D imaging and pulsed and continuous wave Doppler. The Bernoulli equation for valve gradients was breaking news, but for the most part, we didn’t know what to do with Doppler. I thought that my background in applied mathematics and fluid dynamics might help and approached Dr. Arthur (Ned) Weyman at MGH for a 1 year fellowship. He informed me that a one-year fellowship would require me to write a grant to support my salary, but if I would commit to two years, he’d fund me 100%. Two years it was, and what great advice! In two years working with Ned and fellow fellows Chris Choong and Gerry Wilkins (of Wilkins Score mitral splitability fame), we used our disparate talents (Chris in the animal lab, Gerry in clinical echo, and me providing some theoretical underpinnings), to help explain the determinants of the mitral pressure half-time, transmitral filling, patterns of LV contraction, color Doppler jet appearance, the physics of the proximal convergence zone and many others, all while having more fun than we had any right to.

After Eric Topol recruited me to the Cleveland Clinic in 1992, the echo world was exploding with new techniques and applications: TEE, intraoperative echo, stress echo, tissue Doppler, digital echo (yes, we used to read from video tape; kids, ask your parents), strain imaging, 3D echo, contrast echo, and on and on. So many wonderful colleagues and talented trainees, working to make new discoveries, in both basic and clinical research. Along the way, I’ve had the incredible opportunity to make friends all over the world seeing sights I never imagined growing up in Oklahoma. I also met and married my wife, Yngvil, who is the joy of my life, along with our kids. In 2011-12 I was proud to serve as President of the American Society of Echocardiography, a wonderful organization that has provided great opportunities to promote and improve our field.

Now I’ve been at Northwestern for nearly 6 years, combining so many things that I enjoy: valve disease, echocardiography, physics, and pushing the boundaries forward in physiology and cardiovascular imaging. If anything, the echo innovation has accelerated, driven in part by the challenges of interventional guidance requiring cleaner imaging and more intuitive user interfaces. Transducers get more sensitive and processing gets more clever, to the point that it seems we’re violating the physics of ultrasound, thanks largely to the endless increase in computer power (maybe 100,000,000-fold since I saw that first M-mode echo, which was analog, not at all “digital”. It is this amazing computer power that is fueling the tsunami of machine learning coming our way, harnessing the wisdom of millions of well-interpreted echoes and detailed additional clinical parameters to discover subtleties in an image that our eyes simply can’t see. Already artificial intelligence can guide novice acquisition of echoes, quantify LV ejection fraction, detect cardiomyopathies, even tell us the age and gender of the patient! As AI is integrated into echo machines and reading platforms, it promises to make sonographers more efficient with less musculoskeletal strain, allow more insightful diagnoses, and extend the power of expert echocardiography to ER’s, ICU’s, primary care offices, the developing world, even outer space! All in all, it’s been a great career as the “echo guy”, and I can’t wait to see what the future will bring!

I had a deep conviction that I would NEVER want to be the “echo guy”. Well, fast forward some 4 decades, and I guess that’s what I’ve mainly been, and it’s been a fascinating ride, with every year bringing new discoveries and new technological breakthroughs.

James D. Thomas, MD, FASE, FACC, FESC